Jan 22, 2026 – By Zenx News

In a groundbreaking experiment that pushes the boundaries of quantum mechanics, researchers at the University of Vienna have successfully placed clusters of thousands of atoms into a superposition state – the largest such achievement to date. This feat, detailed in a recent study published in Nature, brings us closer to understanding the fuzzy line between the weird world of quantum physics and the everyday classical reality we experience. By demonstrating that even relatively massive objects can exhibit wave-like quantum behavior, the work not only revives the spirit of Erwin Schrödinger’s famous thought experiment but also has profound implications for technologies like quantum computing and advanced sensors.

Superposition, a core principle of quantum mechanics, allows particles to exist in multiple states simultaneously until observed or measured. Think of it as a coin spinning in the air, being both heads and tails at once – but on a subatomic scale. This phenomenon underpins everything from the behavior of electrons in atoms to the power of quantum computers. However, as objects get larger, they tend to lose this quantum “magic” due to interactions with their environment, a process called decoherence. The Vienna team’s experiment challenges how far we can scale this up, showing that quantum effects can persist in systems far bigger than previously thought.

The Science Behind Superposition: From Particles to Clusters

To grasp the significance, let’s rewind to the basics. Quantum mechanics, developed in the early 20th century by pioneers like Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg, describes the behavior of matter and energy at the smallest scales. Unlike classical physics, where objects have definite positions and velocities, quantum particles can be in superpositions – multiple possibilities coexisting.

Erwin Schrödinger illustrated this counterintuitive idea in 1935 with his infamous “cat” paradox. Imagine a cat in a sealed box with a radioactive atom, a Geiger counter, poison, and a hammer. If the atom decays (a quantum event with 50% probability), it triggers the release of poison, killing the cat. According to quantum theory, until the box is opened, the atom is in a superposition of decayed and not decayed, meaning the cat is both alive and dead. Schrödinger meant this as a critique, highlighting the absurdity of applying quantum rules to macroscopic objects. Yet, nearly a century later, experiments like this one are making that absurdity a reality – albeit without harming any cats.

In modern labs, superposition is routinely observed in small systems: single photons, electrons, or even molecules. But scaling it up is tricky. Larger objects interact more with their surroundings – air molecules, thermal vibrations, or stray photons – causing decoherence, where the superposition collapses into a single classical state. The Vienna experiment overcomes this by using ultracold atomic clusters in a highly controlled vacuum environment.

The clusters consisted of about 7,000 sodium atoms each, forming nanoparticles roughly 8 nanometers across – comparable in size to a small protein or virus particle. That’s massive on a quantum scale: the total mass is around 140,000 atomic mass units, dwarfing previous records with molecules of just a few thousand atoms.

How the Experiment Worked: A Quantum Obstacle Course

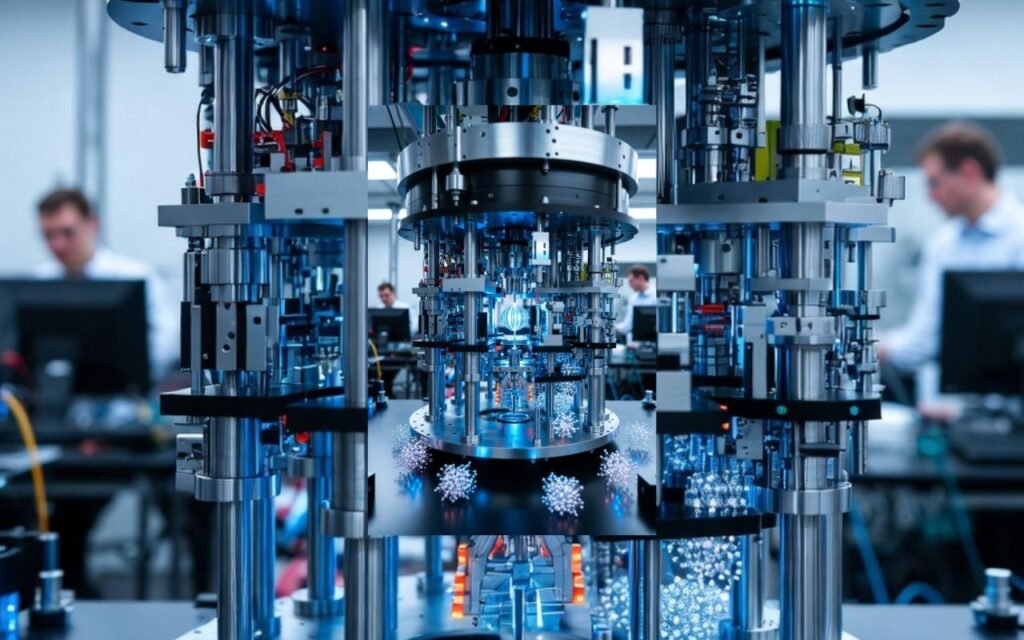

The setup involved a sophisticated device called a matter-wave interferometer, essentially a quantum version of the classic double-slit experiment. In the double-slit setup, particles like electrons pass through two slits and create an interference pattern on a screen, proving they behave as waves. Here, the team adapted this for much larger clusters.

First, the sodium clusters were cooled to a frigid 77 Kelvin (-196°C) and formed into a beam in an ultra-high vacuum chamber to minimize external disturbances. The beam was then directed through three “gratings” made not of physical slits, but of precisely tuned laser beams that act like optical barriers.

- The First Grating: This channels the clusters through narrow “slits” (regions where the laser light doesn’t repel them), causing each cluster to diffract and spread out as a wave. The waves from adjacent slits travel in phase, setting up the superposition.

- The Second Grating: Here, the waves interfere with each other – constructively in some places (adding up) and destructively in others (cancelling out) – creating a patterned beam.

- The Third Grating: This detects the interference pattern by allowing only certain parts of the wave to pass through, confirming the clusters were in a superposition of positions separated by 133 nanometers.

The key challenge was maintaining coherence long enough for the interference to occur. Any tiny disturbance could collapse the superposition. By optimizing the vacuum and temperature, the team achieved a clear interference fringe, proving the clusters acted as waves spread over multiple locations simultaneously.

This isn’t just a lab trick; it’s a rigorous test of quantum theory. The experiment’s lead, described in the Nature paper as S. Pedalino et al., built on decades of work in matter-wave interferometry. Previous milestones include superpositions of fullerenes (buckyballs) in the 1990s and larger organic molecules in the 2010s. But this jumps to inorganic metal clusters, which are denser and more prone to decoherence, making the success even more impressive.

Expert Insights and Broader Implications

Reactions from the scientific community have been enthusiastic. Sandra Eibenberger-Arias from the Fritz Haber Institute in Berlin called it a “fantastic result,” noting it confirms quantum mechanics holds for objects of this size without any unexpected breakdowns. Giulia Rubino from the University of Bristol emphasized its relevance to quantum technologies, saying such experiments help us understand where – if anywhere – quantum rules give way to classical ones.

This ties into ongoing debates about quantum interpretations. Only about 4% of physicists in a recent survey believe in “objective collapse” theories, where superpositions spontaneously resolve beyond a certain scale. Most favor ideas like decoherence or the many-worlds interpretation, where all outcomes branch into parallel realities. By scaling up without collapse, this work supports the latter views and constrains collapse models.

Practically, the implications are huge for quantum computing. Qubits – the building blocks of quantum computers – rely on superposition to perform calculations exponentially faster than classical bits. Current quantum processors handle dozens to hundreds of qubits, but scaling to millions could enable breakthroughs in drug discovery, cryptography, and climate modeling. If natural limits kicked in at smaller scales, it would doom these efforts. This experiment suggests we’re safe for now, but larger tests are needed.

Beyond computing, the techniques could improve quantum sensors for detecting gravitational waves or dark matter, or even enable new materials with quantum-enhanced properties. In biology, understanding quantum effects in large molecules might explain phenomena like photosynthesis or avian navigation.

Challenges and the Road Ahead

Of course, hurdles remain. The clusters are still tiny compared to everyday objects – a far cry from a real cat. Decoherence times are short, limiting practical applications. Ethical questions arise too: as we manipulate larger quantum systems, could this blur lines in fields like biotechnology?

Future work will aim for even bigger superpositions, perhaps with biomolecules or levitated nanoparticles. International collaborations, funded by bodies like the European Research Council, are accelerating this. In the U.S., labs at NIST and Caltech are pursuing similar paths, while China’s quantum programs focus on entanglement in massive systems.

This Vienna achievement isn’t just a record; it’s a step toward reconciling quantum weirdness with our classical world. As Rubino put it, “We’re probing the foundations of reality itself.”

In a year already buzzing with innovations – from AI advancements to space milestones – this quantum leap reminds us that the universe’s deepest secrets are still unfolding. For scientists, it’s exhilarating; for the rest of us, it’s a glimpse into a future where the impossible becomes routine.